Seit 25 Jahren begleitet die Zeitschrift DAS GEDICHT kontinuierlich die Entwicklung der zeitgenössischen Lyrik. Bis heute ediert sie ihr Gründer und Verleger Anton G. Leitner mit wechselnden Mitherausgebern wie Friedrich Ani, Kerstin Hensel, Fitzgerald Kusz und Matthias Politycki. Am 25. Oktober 2017 lädt DAS GEDICHT zu einer öffentlichen Geburtstagslesung mit 60 Poeten aus vier Generationen und zwölf Nationen ins Literaturhaus München ein. In ihrer Porträtreihe stellt Jubiläumsbloggerin Franziska Röchter jeden Tag die Teilnehmer dieser Veranstaltung vor.

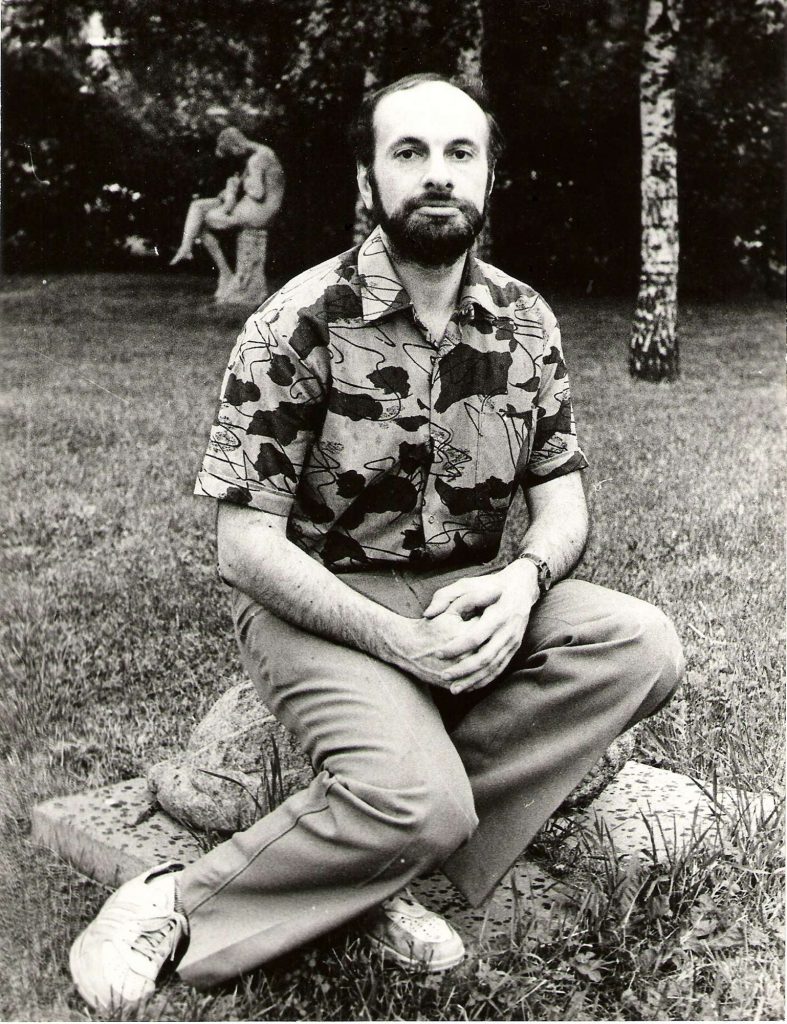

Anatoly Kudryavitsky is a Moscow-born Russian/Irish poet and novelist of Polish/Irish descent. A holder of a PhD from Moscow Medical Academy, he has a background in biology, Celtic heritage, music and literature, and worked as a researcher, as a journalist, as a literary translator and as a magazine editor. Having emigrated in 1999, he has since been living in Dublin. He is a bilingual author writing in English and Russian, and has published three novels as well as seven collections of his Russian poems, the latest title being »New and Selected Poems« (DOOS Books, Moscow, 2015). He has also published four books of his English poems, the latest being »Horizon« (Red Moon Press, USA, 2016), and edited various anthologies. He was awarded several literary awards. His poems and short stories have been translated into fourteen languages. Kudryavitsky is president of the Irish Haiku Society.

Auch Umzüge über Ländergrenzen hinweg können etwas so Schwerwiegendes wie die sogenannte ›Russische Seele‹ nicht gänzlich verändern. Dr. Anatoly Kudryavitsky sprach mit Franziska Röchter über seine frühen Erfahrungen in einem repressiven Land, seine Zwischenstation in Deutschland und die Rückkehr zu seinen wirklichen »roots« in Irland.

The experience of being a blacklisted Samizdat author made me stronger mentally.

Dear Anatoly Kudryavitsky, how many years did you spend in Germany before settling down in Ireland?

I lived in Hessen at the end of the last century, for two and a half years, before I completed my move to Ireland. I spent a year learning German, and could speak it reasonably well at that stage of my life, although my German has deteriorated over the course of these years. If you don’t use a language, you may even lose it, which is rather unfortunate. But it sometimes happens.

You have translated poetry from quite a few European languages into English, and you used to translate poetry from other languages into Russian. What about translating them into German or vice versa?

I mostly translate into English these days. Over the last 12 years I’ve published anthologies of contemporary Russian and German-language poetry; my anthology of modern Ukrainian poetry in English translation is coming out in England this month, and another anthology of Russian poetry, this time comprising minimalist works, is due from the same publisher in early 2018. I’ve also published my translations from Polish, Swedish and Italian poetry into English. Unfortunately, my knowledge of German is not good enough to be able to translate poetry into this language. As for translating from German, I’ve published an anthology of German-language poetry in English translation, »Capering Moons« (Doghouse Books, Kerry 2011), which I co-translated with my daughter Yulia; she grew up in Hessen and is a native speaker of German currently based in Berlin.

Apart from your Celtic ancestry – your mother was half-Irish – what motivated you to move to Ireland?

As they say here, Irish blood is strong, and returning to the country of my ancestors was always high on the list of my priorities. I am glad that I finally accomplished it. Another thing, I began writing poetry in English in 1992, and so living in the country where English is predominantly spoken, was important to me. This was probably the main reason why I returned to Ireland, exactly one hundred years after my Irish grandfather left the country.

If you don’t rely on editors to pinpoint what you can improve in your writing, you are the only judge of your work, and you learn to be harsh on yourself.

You hold a PhD from Moscow Medical Academy, and you used to work as a researcher. What made you become a writer? And how were you affected as a writer by not being permitted to publish your work openly under the Communists, i.e. at the early stages of your career?

It is difficult to say what made me become a writer – perhaps I had something to say, had a message to get across »urbi et orbi«? The reason for me being blacklisted was my involvement – not a very deep one, mind you, – with the Russian dissident movement. My first short story got published in a Russian magazine in 1989, when Perestroyka began. So I can say that I developed as a writer rather late. In different circumstances this could be avoided but then, this is just the way it happened.

How did this experience of being a blacklisted Samizdat author affect your further life as a writer and also your private life?

I guess this experience made me stronger mentally. If you don’t rely on editors to pinpoint what you can improve in your writing, you are the only judge of your work, and you learn to be harsh on yourself. This always helps. On the other hand, the habit of hiding one’s inner thoughts makes this person rather reclusive, and I guess this is what has happened to me.

How often do you visit Russia at present, and what are your feelings towards this country, particularly if you take the actual political developments into consideration?

I don’t visit Russia, even though I love the country; I haven’t been there since 2000. My books keep coming out there, and I am happy with that. I will be delighted to visit Russia again when democratic priorities in this country are restored. It looks like I will have to wait a little bit longer.

I am afraid I am finished with writing in Russian.

Since you live in Ireland, your poetry has predominantly been written in English, whereas you continued to write your fiction in Russian. If you were asked to tag the themes and topics of your novels and stories, how would they read?

I am afraid I am finished with writing in Russian, as I haven’t written any work of fiction for quite a few years now. It is difficult to write in the language that isn’t spoken around you. But I am very much at home with writing poetry in English, especially experimental poetry. The topics of my novels? Let’s see … Words like »history«, »freedom«, »dignity«, »nature«, »parallel reality« immediately spring to mind, but then I guess, all people think about these things, don’t they?

You were the founder and first President of the Russian Poetry Society. When did you start with this and what was the aim and the purpose of establishing this society?

It was an attempt to establish an association of poets not under the auspices of the Writers’ Union, which was always keen on keeping writers under control. We wanted to escape that control, and so we did. The Society still exists, and they publish a good poetry magazine, »Zhurnal Poetov«, where I am on the editorial board. This magazine is one of only a few Russian publications that are open to experimental poetry.

English seems to be rather suitable for haiku writing.

You are also Chairman of the Irish Haiku Society. How come that you developed such a preference for this form of miniature poetry that originates in the 17th century and took root in Ireland in the 1960s?

The late Russian poet and academic Vera Markova, a friend of mine who had also been a friend of the legendary poet Marina Tsvetayeva, was the person who introduced me to haiku in the early 1990s, and so started me on an unexpected journey. She translated all the Japanese masters of haiku into Russian, and her translations were very popular in Russia. As for me, I have never written haiku in Russian, and I still don’t know how to do it properly, however English seems to be rather suitable for haiku writing. Over the last ten years I have published three collections of my haiku and also edited two anthologies of haiku writing from Ireland.

Haiku in Ireland

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HrgCo9PstnQ

Your recent Haiku anthology »Between the Leaves« was published in 2016 by Arlen House. How does it differ from your first Haiku anthology?

The first anthology, »Bamboo Dreams« (Doghouse Books, Kerry 2012), gives an account of the history of haiku writing in Ireland and has poems written as early as in 1960s and 1970s, as well as some recent work. »Between the Leaves« is an anthology of new haiku writing from the island of Ireland.

Surrealism is mostly about irrational juxtaposition of images and sounds; if it is done properly, the outcome can be a beautiful poem.

In July 2017, the first issue of your very young online poetry magazine »SurVision« appeared. It is an international biannual online magazine that publishes Neo-Surrealist poetry in English. What is your personal definition of Neo-Surrealism in literature? What gave you an idea of becoming a magazine editor?

Well, I edited literary magazines ever since 1989, with a couple of intervals, so this is something I am well accustomed to. There was a niche for specifically Surrealist English-language poetry magazine, as the ones that existed before, like »Exquisite Corpse«, are now all gone. Surrealism is mostly about irrational juxtaposition of images and sounds; if it is done properly, the outcome can be a beautiful poem. Neo-Surrealism is Surrealism today.

Now some very profane or basic questions, nonetheless important to understand a poet’s nature. What do you prefer: Borschtsch, Pichelsteiner or Irish stew?

Irish stew.

Baltica, Warsteiner, Kilkenny or even Guinness?

Kilkenny, especially if there’s no good cider on offer.

Watruschka, Schwarzwälder Kirschtorte or Fudge?

Lebkuchen!

When you think back to Russia: what are the first three words that come to your mind?

Expanses. Silence. Survival.

What do you mainly and instantly associate with Germany (three words?)

Forest. Kneipe. Dada.

And the first three words on Ireland?

Mist. Shamrock. Fiddle.

I am mostly reading experimental English-language poets these days.

Which poets do you prefer reading: Pushkin, Heine or Yeats?

Of the Russian poets, I keep coming back to Khlebnikov; talking about the German ones, it would be Paul Celan, and of the Irish poets, it has to be, indeed, Yeats. I have to say that I am mostly reading experimental English-language poets these days; at the moment I have a book by the American poet Dean Young on my desktop, and I am thoroughly enjoying it.

Dear Dr. Kudryavitsky, thanks a lot for this interview.

Anatoly Kudryavitsky (Editor)

Anatoly Kudryavitsky (Editor)

Between the Leaves

New Haiku Writing from Ireland

Arlen House 2016

128 pages, Paperback

ISBN: 9781851321599

Unser »Jubiläumsblog #25« wird Ihnen von Franziska Röchter präsentiert. Die deutsche Autorin mit österreichischen Wurzeln arbeitet in den Bereichen Poesie, Prosa und Kulturjournalismus. Daneben organisiert sie Lesungen und Veranstaltungen. Im Jahr 2012 gründete Röchter den chiliverlag in Verl (NRW). Von ihr erschienen mehrere Gedichtbände, u. a. »hummeln im hintern«. Ihr letzer Lyrikband mit dem Titel »am puls« erschien 2015 im Geest-Verlag. 2011 gewann sie den Lyrikpreis »Hochstadter Stier«. Sie war außerdem Finalistin bei diversen Poetry-Slams und ist im Vorstand der Gesellschaft für

zeitgenössische Lyrik. Franziska Röchter betreute bereits 2012 an dieser Stelle den Jubiläumsblog anlässlich des »Internationalen Gipfeltreffens der Poesie« zum 20. Geburtstag von DAS GEDICHT.

Die »Internationale Jubiläumslesung mit 60 Poetinnen und Poeten« zur Premiere des 25. Jahrgangs von DAS GEDICHT (»Religion im Gedicht«) ist eine Veranstaltung von Anton G. Leitner Verlag | DAS GEDICHT in Zusammenarbeit mit dem Kulturreferat der Landeshauptstadt München. Mit Unterstützung der Stiftung Literaturhaus. Medienpartner: Bayern 2.